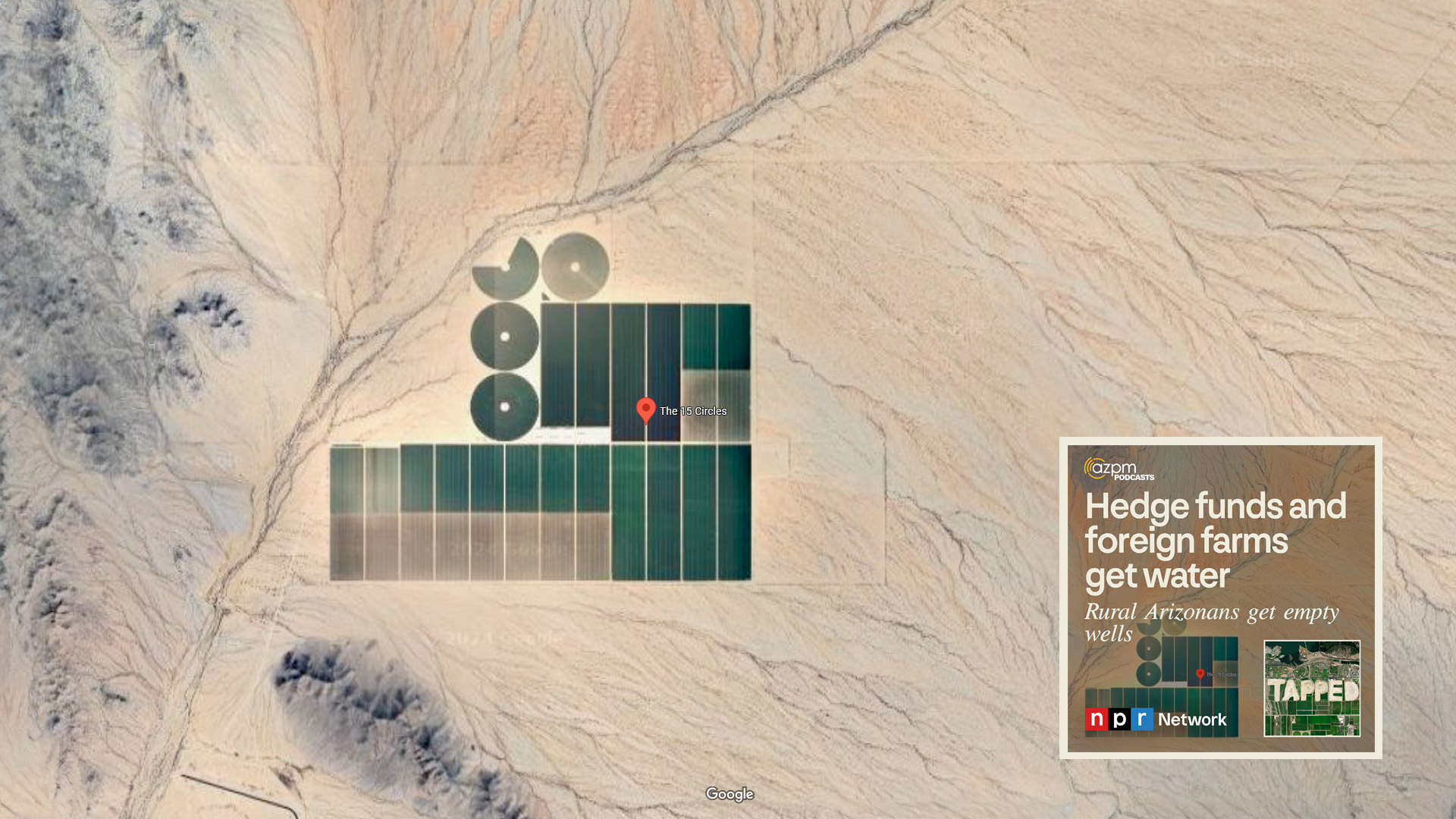

This map shows an area of land identified by locals as the 15 Circles. State data still shows this land as being leased by Fondomonte, the Saudi-backed alfalfa farmers.

This map shows an area of land identified by locals as the 15 Circles. State data still shows this land as being leased by Fondomonte, the Saudi-backed alfalfa farmers.

Tapped: Season 3 Episode 07

Saudi involvement in western Arizona's rural La Paz County is already well known. But they are not the only non-local interest in the area making use of water. Hedge funds, foreign countries, and green energy interests want to turn rural groundwater into dollars, and they have a lot of ideas how to do it.

Zac Ziegler: Let's go back in time, back to when Arizona was rethinking its water laws during the negotiations that eventually brought the Central Arizona Project, the state's 300+ mile canal that transports Colorado River water, into existence.

Robert Glennon is a Regents Professor Emeritus and water law expert at the University of Arizona.

RG: In the late 70s, when Babbitt was pushing the Groundwater Management Act.

ZZ: He's referring to Bruce Babbitt, the then-state Attorney General. He eventually went on to become the governor and subsequently the US Secretary of the Interior.

RG: The rural parts of the state wanted no part of it. They wanted to be left alone, and they thought that this was just going to be complicated government regulations, and they just didn't want it. But I think their views have changed."

(music fades in)

Holly Irwin: Change needs to happen.

Christopher Conover: That's Holly Irwin, the La Paz County Supervisor we heard from last time.

HI: But it's frustrating when you try to work on a piece of legislation and we can't even get a hearing down at the legislature.

CC: And she's not alone. That legislation she mentions was the work of several rural county supervisors.

So what changed their minds?

RG: With Fondomonte and other Saudi interests coming in, and wells drying up. I mean small domestic wells drying up because these huge ag wells have come in.

ZZ: We talked about those Saudi wells last time, but like we said, they're not alone.

This is Tapped, a podcast about water, I'm Zac Ziegler.

CC: And I'm Christopher Conover.

So who else is drying up the aquifers in rural Arizona? And what can be done about it?

(music fades out)

ZZ: As you walk up to Gary Saiter's door, you wouldn't believe him when he says he and his wife only have one cat, a sweet old lady named Kimchi.

GS: "She had a partner of 15 years. Wasabi was a 25 pound Siamese, and he died about a year and a half ago, and it took her a year to get over it, but she's about 16 now."

ZZ: There's a clowder of cats that hang out in his yard in Wenden, helping keep the pests out of the gardens where he grows much of his produce.

CC: But we didn't come to Gary's house to talk about cats…

VIEW LARGER Gary Saiter, head of the Wenden Domestic Water Improvement District

VIEW LARGER Gary Saiter, head of the Wenden Domestic Water Improvement District GS: I am the chairman of the board for the Wenden Domestic Water Improvement District and the general manager as well, have been for about the last eight years.

CC: Like many residents in La Paz County, Gary retired there. He was an executive with Sherwin Williams and got swept up into civic life, serving on the school board and various other spots before becoming a part of the public water district.

GS: I didn't know anything about water eight years ago. I know a lot now, and probably more than I ever wanted to, but it's part of the job, and I feel that I'm doing something good for the community, and having opportunities to speak out about water issues in our valley with our aquifer, it's important to me.

CC: That aquifer is the McMullen Valley Basin. It's an area that people have farmed for decades. But farming there has changed.

GS: So, about 2016 they sold 12,000 acres to international farming, which is an investment company in North Carolina. It operates under the name of Desert Valley Farms.

ZZ: Gary and other locals say that land was being leased by Al Dahra Farms, a company with links to the United Arab Emirates. That company owned a small parcel in the area.

GS: When the investment company bought the properties, all of a sudden, we stopped having melons, and we stopped having people food.

And they started growing alfalfa, which Gary says has notable effects on the aquifer around him.

(music fades in)

GS: Wenden is, according to ADWR in a subsidence bowl.

ZZ: Subsidence is when land collapses or drops because it is no longer supported. In this case, that land was supported by the water in the aquifer. So, as the water level drops, so does the land above it.

The water district Gary oversees in Wenden serves a few hundred people. But now they are seeing problems that tie back to how much water is coming out of the ground.

GS: I've had a 31% increase in water leakage, water leaks that needed to be repaired in my distribution system in the last calendar year, and it is because of land subsidence, and the mains have done pretty well with the sinking. It's the service lines that come off the mains. I mean, we do three, four repairs a month.

CC: Wenden is a small town…so the subsidence isn't just an issue hitting the municipal water system…it can be personal. Gary's wife owns a shop in town and has seen the effects firsthand.

GS: I can show you in between the floor and the sideboards, you know, on the floor, you know, gaps like that. The kitchen area in the back is sinking like that. She's on top of a sinkhole. It's 100-year-old building. In the last 15 years, it sunk three and a half feet.

CC: Gary has been able to cover costs for repairs without any major rate increases thanks to grants. In fact, the Wenden DWID, as it's called, is adding some smart monitoring so it can more quickly detect leaks thanks to grant money.

But, he says major repairs or having to deepen a well would be hard to pay for when your customer base is a few hundred people who on average pay about $60 a month.

GS: You're talking big money when you start to think about this if the farm is going to drop an 18-inch commercial well, 1500 or 1400 feet. It's $1 million. now, I don't have anybody in my district that obviously worries about water, because I make sure they have it.

CC: And the problem with subsidence goes beyond hassles for a water company or a building that's having foundation issues. Remember subsidence means the water table is dropping.

GS: On a private well, they're usually three, 350 feet deep. A lot of those have gone dry some are in jeopardy. And see an aquifer isn't like a lake. It's depending on where you, you know, it's different levels depending on where you, where you drill down. But a three-inch residential well, going down 500 feet, 75 grand, most people can't afford that.

(music fades out)

VIEW LARGER Kimchi, Gary Saiter's cat.

VIEW LARGER Kimchi, Gary Saiter's cat. ZZ: Right after we left Gary . . . and Kimchi . . . in Wenden, we headed to a diner in Quartzite to meet with Kari Ann Noeltner. At the time she was running for a seat on the La Paz County Board of Supervisors, but she lost to an incumbent in the primary.

She moved to Arizona after working in the fishing industry in the Pacific Northwest. She tried Phoenix first but decided that she needed a little more space, so she moved to the community of Bouse.

KN: We've been out here for five years, and from year one to year now, we're definitely going through filters, through our filtration system, much quicker than we were before. There's a lot more sediment that's coming up, and so that's that's concerning. I don't know that it's related to our our aquifers going down, but I know that I don't have an answer for it."

ZZ: She says her well goes down 265 feet, a little deeper than the county’s average, and her water level is probably around 180 feet deep.

KN: We've dropped at least a foot in the time that we've been there. And, you know, these commercial, industrial wells are down around 1200 feet, if they can tap in that far into it, we have an industrial and a commercial well right in front of us and the property in front of us. And I think that was the other, the other part of that, you know, those wells went in, and we questioned why they put them in.

ZZ: And part of that answer is a larger problem for La Paz and other rural Arizona counties. Kari Ann's example came when she spotted a new commercial well being drilled near her home.

Bouse resident Kari Ann Noeltner

Bouse resident Kari Ann Noeltner

KN: And when I called, What is it well 55 and said, you know, how can somebody get a permit to put that huge of a well in, she was like, Oh, you could do that on your property if you wanted to. I'm like, I could put an industrial or a commercial depth well on my little 10 acres. And she's like, yep, you guys aren't under any regulations. That's scary to me that every time we see a well trigger out in our area, we go on to the property, we're like, what do you drill in the well for? Who are you? We don't know.

CC: We don't know…that too is a problem. The newest mystery land owner in La Paz and why they spent 100 million dollars to get that land…that's after the break.

[NPR Politics promo]

ZZ: This is Tapped, a podcast about water. I'm Zac Ziegler.

CC: And I'm Christopher Conover.

ZZ: When we left, Bouse resident Kari Ann Noeltner was telling us about how a new commercial well in her neighborhood was concerning for her.

But what was more concerning was an official’s reaction: you too can build one of those, if you want.

We can't 100% pinpoint which property she was talking about, but just down the road is a spot that locals have identified on Google Maps as The 15 Circles.

The 15 Circles.

That area is land that state data still shows as being leased by Fondomonte, the Saudi-backed alfalfa farmers.

But as we have mentioned…they are not the only big, non-local farmers in the area. Right down the street from Gary's property is land that he mentioned was leased by a U-A-E-based company and owned by a North Carolina-based investment fund.

GS: They have recently, in the last year, cut back half of their land use. They've moved all of their storage out. It looks to me like they're planning on shutting down, and I do know that the North Carolina company wants to sell the property.

ZZ: And sell they did…it turns out the deal closed the day we were sitting with Gary just a few hundred yards away.

On July 1, Arizona Valley Farm sold nearly 13,000 acres to a company called Emporia III, LLC. The price tag: 100 million dollars. That's more than twice what Fondomonte paid for its 10,000 acres.

That land virtually surrounds Wenden, the community Gary calls home.

Corporate records on Emporia trace back to offices on Madison Avenue in New York City.

(music fades in)

Those offices are the home of a company called Water Asset Management LLC.

We reached out to the company multiple times but did not receive replies to our calls or emails.

CC: Now if you run that company through the Securities and Exchange Commission and the New York State office that regulates corporations, you will find a few interesting things. First, they are registered in Delaware…a U-S haven for corporations that don't want a lot of information out in public…they also have ties to a company registered in the Cayman Islands…an international haven for corporations.

The information that is available from the SEC shows that they are listed as what most people call a hedge fund but are officially a private equity firm. And they are declining to disclose the size of the issuer, something firms like that can legally do.

Water Asset Management's website has a section called Water Investment Opportunity that says "Investing in the water industry provides the opportunity to generate returns that exceed the market while simultaneously delivering measurable positive impact."

They don't list their holdings on the website…to get that information we would have to be investors…and let's be honest we work for a public media station so investing in private equity firms is a little out of the newsroom and personal budget.

ZZ: The land that WAM purchased in La Paz County isn't its only holding in western Arizona.

It also owns more than 500 acres in Mohave County under two other LLCs and almost 1,100 acres in Yuma County under a few other LLCs.

We should note the way water law in western Arizona works.If you own the land… for the most part, you own the water rights.

But, the land that they own in La Paz County has a special designation.

Two of the major aquifers in the area are designated as transfer basins. That means water can be transported out of the basin and into other places.

Gary Saiter, who runs the water district in Wenden illustrated how this could work using a previous owner of some of the land, the City of Phoenix.

GS: Since 1983 when the water laws were put into place, it owned about 12,000 acres here in this valley. They owned it for one reason, that was water.

(music fades out)

Ultimately, in about 2016 they decided, well, you know, it would be too expensive to transport it, even though, according to the legislature, this aquifer is what they call a transport aquifer, meaning that the legislature says screw the people who live there. We don't really care. They can transfer water out of here and send it to a metropolitan market, and the people who live here have no say.

CC: Now, we're going to take you back to Episode Four of this season, when we talked about the Central Arizona Project.

Just a note, the Central Arizona Project is a sponsor of this show, but they have no editorial control.

There was a quick detail that Rich Weissinger, CAP's Director of Field Maintenance, mentioned during our interview when talking about changes to the agreement that governs what can go into the CAP.

RW: That really is allowing us to use non-project water, non-Colorado River water, in the system to move that water. So where a user might have access to water somewhere else, say a municipality, so they want to get that water from where that is. And basically exchange it for water down the road or down the canal, it allows us to do that. So it sets some water quality standards, sets water quality standards for incoming water, non-project water into our system.

CC: We couldn't find evidence of any trying to put non-Colorado River water in the CAP yet, but we did find something close.

(music fades in)

The Guardian reported in April that a different hedge fund, Greenstone Resource Partners LLC, had bought land about a decade ago near the community of Cibola, which sits in La Paz County along the Colorado River.

ZZ: That land came with an allocation of river water.

Rather than pull that allocation out near the farmland, Greenstone petitioned to pull the water out at Lake Havasu, namely at the Mark Wilmer Pumping Station, the entry point to the CAP.

2,000 acre-feet of that water was sold to Queen Creek, a suburb of Phoenix.

A federal judge ruled that the transfer was done without proper environmental review and put it on hold pending a more thorough review by the Bureau of Reclamation.

CC: Mother Jones reported at about the same time that the Water Asset Management Group's holdings in Mohave County that we mentioned earlier also have a Colorado River water allocation.

(music fades out)

Then there are also what some might call more well-intentioned uses of groundwater in this area, like a green energy operation in the Renegras Basin, where Kari Ann Noeltner lives.

KN: On that basin we've got Fondomonte is still currently on that. We have another company, Heliogen, who was going to tap in for hydrogen production. We hear now that maybe they won't, but we're waiting for the written rule on that.

ZZ: Heliogen is a green energy company, which is leasing 3,300 acres of federal land in La Paz County near the community of Brenda. The land is part of an area designated for green energy projects.

We asked the company about its operations in La Paz County. They told us that they are opting out of green hydrogen production on this property and will instead focus on only solar.

A statement sent to AZPM said in part "This decision was based on a number of factors, including our careful consideration of community concerns, particularly regarding water usage, as the revised project scope reduces water usage by approximately 80%. Our updated proposal is now under review."

They did not specify a concrete amount of water they would have or will now use, even after we sought clarification.

We spoke with County Supervisor Holly Irwin to double-check this, and she said the company made the switch, largely because people were concerned about how much water the project would take in an area where residents, including Kari Ann Noeltner, are asking how much more they can afford to give up.

A map of Water Asset Management and other company holdings. Click on the faucets for more information.

KN: But I think as a resident on that basin, our big concern is that we are really being looked at because of our amount of bare land, and according to Heliogen, and our abundance of water, which we couldn't quite figure out, but we're being looked at for that green energy type industry. And you know that concerns me, for how many more wells are going to get tapped in without us really having any say about it?"

CC: Robert Glennon, our University of Arizona water law professor from earlier, sums up the problem.

RG: "It's 'I have a right to pump until and unless a bigger well is installed on the property next to me, and they pump away and my well goes dry, and then what do I have? You have nothing. You have no recourse. So it's kind of a circular firing squad."

**CC: So what are the residents of rural Arizona to do when Wall Street or a rich foreign government comes to town and starts buying land and water rights?

KN: You know, we just we want some reassurances that there is something in place that we are being looked after, because that is one thing that I don't think I could ever become a master in, is drilling my own well and continuing to go deeper and deeper, and it takes time to get a well digger out there. How many days is it before you die of thirst, you know? It's not an immediate fix.

ZZ: For some like, La Paz County Supervisor Holly Irwin …the answer rests at the state capitol…

HI: It's going to take our leaders to help us, you know, I'm just one supervisor, you know, I'm one that's been fighting this fight. There's days I go home crying, you know, there's days I get up just being so angry the next day, and just when you think you're finally getting to a point where, oh my gosh, maybe we can finally get some legislation passed, and then that fails.

ZZ: But Gary Saiter is not so sure the answer is in the halls of power in Phoenix.

GS: The problem's the legislature. The legislature refuses to enact any controls over 80% of the land in Arizona, which is all the rural areas. That's the problem. Has been the problem from the beginning.

(music fades in)

ZZ: So why haven't the state's elected officials done anything? That's next time.

CC: Yep…another cliff hanger.

ZZ: Tapped is a production of AZPM News.

This episode was written and reported by me, Zac Ziegler, and our News Director, Christopher Conover.

Paola Rodriguez edited this episode.

Our theme music and some interstitial music is by Michael Greenwald.

Visit our website in the podcasts section of azpm.org for pictures, links, and more.

Thanks for listening.

(music fades out)

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.