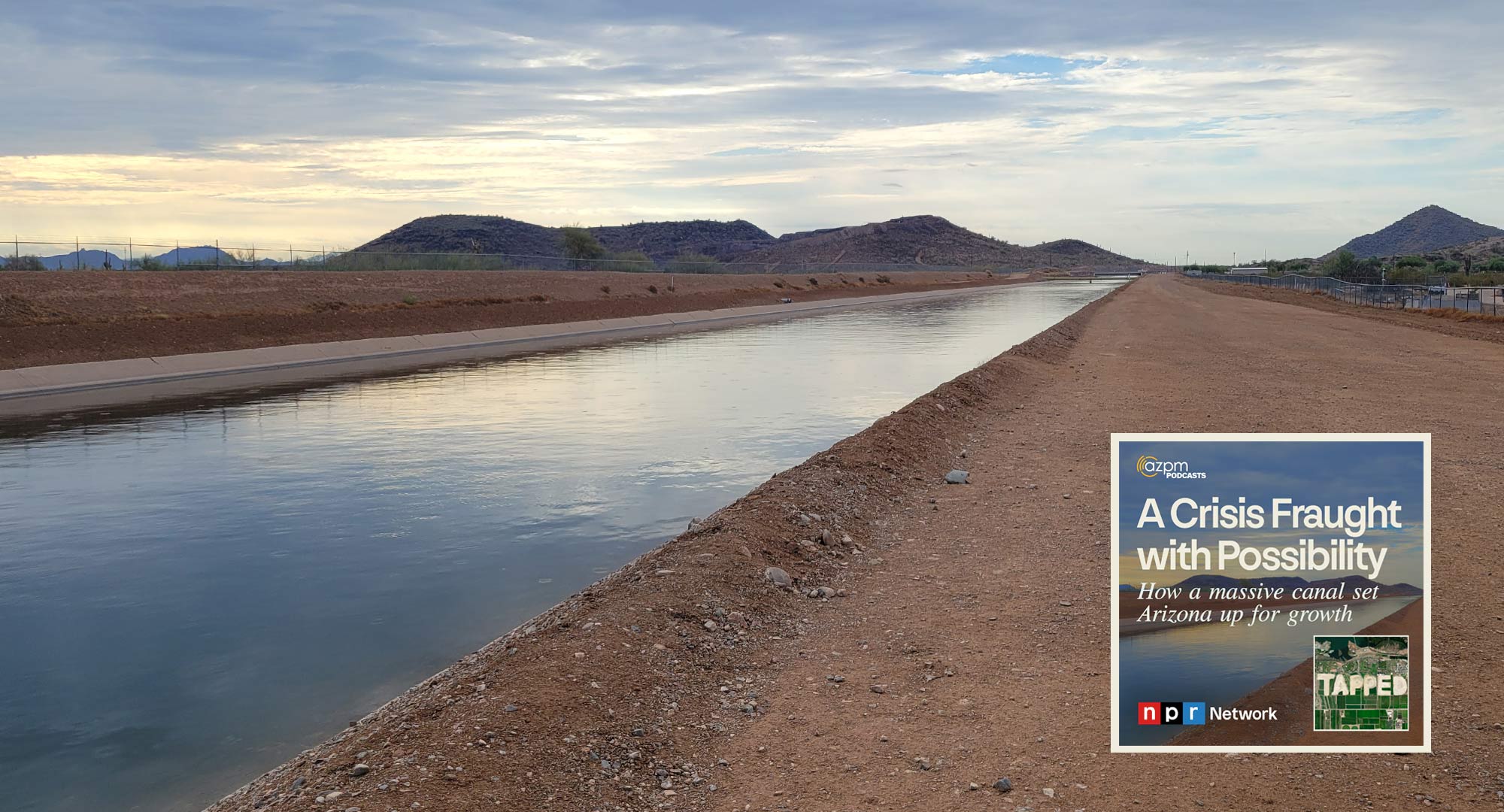

The Central Arizona Project canal just north of CAP headquarters near Phoenix.

The Central Arizona Project canal just north of CAP headquarters near Phoenix.

Tapped: Season 3 Episode 04

In the 1960s, Arizona was facing a crisis. Its aquifers were depleting and its ground was sinking. That issue prompted a major infrastructure project that would forever change what was possible in the state, a 336 mile system of canals that take a big part of the state's Colorado River water allocation and diverts it to Phoenix and Tucson, as well as farmland in Central Arizona. This week, we look at how the Central Arizona Project came to be, and what it means to the state. .

Transcript

Zac Ziegler: We're sitting in a car in front of the Mark Wilmer Pumping Plant on the southern edge of Lake Havasu. The plant is named for an attorney who argued in front of the Supreme Court that Arizona should be able to keep its full allotment of Colorado River water.

Christopher Conover: This facility pulls much of Arizona's allocation of the Colorado River out of the reservoir and pushes it into the Central Arizona Project. The catch in between are the Buckskin mountains. So six pumps push the water up 800 ft at a pace that could fill an olympic size swimming pool in under 30 seconds.

The Mark Wilmer Pumping Station starts Colorado River water on a 336 mile journey by pushing it up a mountain range near Lake Havasu.

The Mark Wilmer Pumping Station starts Colorado River water on a 336 mile journey by pushing it up a mountain range near Lake Havasu.

From there it travels down 336 miles of canals, more pumping stations and other infrastructure where it feeds everything from farm fields to the state's two largest metro areas. This is Tapped, a podcast about water. I'm Zac Ziegler.

CC: And I'm Christopher Conover. The bill to start work on the CAP was signed by President Lyndon Johnson in 1968. Work began in 1973 and took about 20 years to complete

So, as the future of Arizona's share of the Colorado River is debated, what does that mean for the state's largest water infrastructure project?

[music fades out]

ZZ: Tell me real quick, just to start off, where we are here.

Rich Weissinger: Well, we're in North Phoenix. Right about kind of the halfway point of our system, Central Arizona Project, we're at our headquarters facilities.

ZZ: That's Rich Weissinger, director of field maintenance for CAP.

Rich was showing me around that stretch of the canal. But before we get to that, a quick acknowledgement. The Central Arizona Project is a sponsor of Tapped and AZPM, but we treat them just as we treat any other company.

And this topic was one in the planning well before they agreed to sponsor the show. In fact, it was nearly the topic of an episode last season when we looked at water infrastructure.

The water at this portion of the canal moves at around three or four miles per hour.

RW: We use volumes, and it's cubic feet per second. So the capacity of our canals is about 3000 cubic feet per second. But it's moving pretty quick. You know, some of the other canal systems within Arizona are much, much slower. Much slower and not as deep canals. These are 16 feet deep, 32 feet across. So good size canal. So a lot of water. When you're talking about the amount of water we move from, from the start of our system. It's about today, as we look at it, just under a million acre feet of water a year that will move along the system.

CC: A million acre-feet, that's about 325 billion gallons, enough to cover the state's household water usage for a year and three months.

Getting to the point where the CAP was moving that much water took decades, with the starting point happening in a piece of legislation you heard about in the first episode of this season.

RW: So 1922, the Colorado River Compact was created that basically divided up the states or divided up the allocation of the Colorado River. It created the upper and lower basin. Fast forward many years, lots of negotiating and lots of we'll call it fighting over water. In 1964, I believe, Arizona's apportion was finally ratified. And that was 2.8 million acre feet.

CC: That was the first agreement that benefited Arizona.

RW: That was just to get access to the water, right? That 2.8 million acre feet for Arizona, needed some way to bring that into central Arizona, so we didn't have an infrastructure. So in 1968, Lyndon Johnson, President Johnson at the time, signed the Colorado River Basin Act, which authorized the building of the CAP."

CC: In an oral history from the CAP, Bruce Babbitt, the governor who oversaw much of the construction of the project, and was the US Secretary of the Interior when it was finished in the 1990s, says it was only part of the talk. There were other proposed projects, including a dam that would have flooded 15,000 acres.

Former Arizona Governor and US Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt.

Former Arizona Governor and US Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt.

BB: It was a very difficult time because the thinking of the water establishment was Orme Dam, now largely forgotten, but Orme Dam was the Holy Grail of the water establishment. We've got to have it. Yes, it's going to flood out the Fort McDowell reservation, but that's the price of progress.

ZZ: The Orme Dam was a project that would have built a reservoir where the Verde River empties into the Salt.

The fact that it would have flooded tribal lands was part of why President Jimmy Carter pushed back on the dam. It became stuck in limbo and was eventually left out of the CAP system.

CC: As Babbitt related in that oral history, coming up with a management plan for Arizona's water was not easy but it had to be done. And a major player in how it got done was Carter's Interior Secretary, Cecil Andrus.

BB: In early summer of 1980, we marched out of his room with this complete.

[music fades in]

We created the Department of Water Resources, blended all the stuff into it, wrote a groundwater code, set up the active management areas, set all these goals, quantified water rights. 25 years later, it hasn't been duplicated anywhere else in the country.

CC: He says the plan they wrote was more than just an accomplishment to get water to Central Arizona.

BB: It was testimonial to a lot of things. We'd been painted into a corner by a combination of state court decisions and problems over this overdrafting and a quarrel between the mines and the cities, which the courts had basically made a bunch of conflicting decisions, scrambling it all up. This provision in the CAP authorization saying you've got to do something. Finally we've got the Secretary of Interior who says, 'Hey, you've got to do something to control over drafting.' Just a crisis made just fraught with possibility. It was a great moment.

CC: That crisis was the state's aquifers under Arizona's major cities.

BB: When agriculture came up, particularly with the invention of really good water pumps, which sort of came in, in the 1940s right before and after World War II, it became really economical to extract these vast amounts of water and the cotton industry just came up like crazy, covered Pinal County, Maricopa extended way beyond the boundaries of the Salt River Project.

ZZ: The Salt River Project is another large canal system in Arizona that acts as both a water and electric utility, thanks to the hydro-electric dams it uses to store water from other rivers that exist in the state's north.

BB: "The pumping down of these basins. Just, you know, going to bring an end to the whole thing you can see in southern Pinal County, a lot of areas that went out of production. The great cotton boom around Eloy and all that area is just tumbleweeds today, because they pumped down the groundwater to the point that it was no longer economically useful, and it was simply going to destroy the resource."

[music fades out]

TR Witcher: Most of the water on the river goes to agricultural use.

That's TR Witcher, a contributor to Civil Engineering magazine, where he wrote an article about the CAP.

TW: Carving up 190 miles of the desert. And then, you know, you've got 174 miles of concrete lined, open channel. You've got tunnels, you've got pumping plants. They had to take water out of Lake Havasu, and, you know, somehow lifted up 824 feet, 66,000 horsepower pumps. I mean, just getting the water up to get it into this long channel. And that was only one of the channels. So, you still had, you still had the awkward duck to get into the Fannin McFarland aqueduct that carries water southeast of Phoenix, and then the final, the Tucson aqueduct, 87 miles bringing water into Tucson. I mean, that's a monumental undertaking."

And, as Rich Weissinger says, that work wasn't cheap.

RW: This was built by the federal government, the Bureau of Reclamation. The Central Arizona Water Conservation District was created to operate and maintain the system and to repay it. So it was what $4 billion initial costs, you know, that's 19 73 dollars. And we have a repayment of about 1.6 billion to the federal government for that.

CC: And keeping it going isn't easy either.

Bill Wheeler: Nothing in that system comes off the shelf.

CC: That's Bill Wheeler, a Tucson-area civil engineer who served as the executive director of the Central Arizona Project Association until 2003. He gave an oral history to CAP.

BW: It's all designed from scratch because it's bigger and more complex than anything that is in the hardware store on the shelf.

ZZ: Because of the one-of-a-kind nature, Rich says, almost everything that goes into fixing the CAP has to be custom made.

RW: We do have a full service machine shop, that we can create parts shafts, bearings and things like that. We can actually create our own because you can't just go buy these things off the shelf.

ZZ: That's part of the massive operation that includes training up people in the trades: electricians, pipefitters, machinists.

In all the CAP employs between 400-500 people, be they trades people, engineers, or the other jobs you'd expect from a large employer, H.R., accountants, De'Ette, the communications person who introduced me to Rich.

All of that to keep these canals full. And they do stay full, he says, even when the amount of water feeding into the system drops. The CAP's main reservoir, Lake Pleasant, does go up and down, but water just moves through the canals at a more leisurely pace when there's less water.

RW: It's kind of and old joke we have, not lower but slower. And so it's important that we have kind of a consistent level in the canal from an infrastructure perspective, you don't want to constantly be raising and lowering the canal, because what will happen is the panels, it's concrete lined, the panels will actually buckle if you lower it to faster, or raise it too fast. We have to be careful of that, so the idea for our operators is to manage that flow with a series of strategically placed check structures, big gates that regulate the water flow. So as a customer downstream maybe doesn't take water, they can continue to regulate the flow so it maintains that level in the canal.

CC: By the way, some time ago, we had a listener ask us a question about how water gets out of the CAP and the Colorado River to the right places. Those gates that Rich mentioned, that's how.

Water is measured as it flows through a gate, and they can be opened and closed to increase or decrease how much water is leaving the canal or reservoir and going to each customer.

And CAP is kind of like your water company too. They have rates…but we are going to keep it simple since their rates are in acre feet and your water company charges you based on cubic feet and there are a lot of other fees…just suffice to say they're likely notably cheaper than what you'd pay, like, about 3 percent of what our local utility, Tucson Water's customers pay, but that's for untreated river water.

ZZ: There's a bulk discount that's WAY better than what you get when you head to a warehouse store.

Now that operation gets water to about 80 percent of the state's population, Rich says, breathing life into a large portion of Arizona.

Well, water is kind of a lifeblood of the desert, right. And we wouldn't be here, I think, without the Central Arizona Project pumping life into the communities that it serves. And I think that's probably one of the biggest, biggest takeaways for me, the benefit, it has, I know, ASU did a study quite a few years back the economic impact that the CAP has had to the valley. And I'd be remiss to tell you numbers right now.

BC: But we can…right after this break.

[NPR promo]

ZZ: This is Tapped, a podcast about water. I'm Zac Ziegler.

CC: And I'm Christopher Conover.

ZZ: Just before the break, we heard about a report from Arizona State University that studied just how much the CAP has helped Arizona's economy.

[music fades in]

CC: That report came out in 2019, and looked at the 20 years of construction, the water it delivered from 1993 to 2017 and the operations of the company from 2011 to 2017.

It estimates that the CAP has contributed $2 trillion to Arizona's Gross Domestic Product in that nearly half-century timeframe.

At the time the canal began operating, about three-quarters of the water it was delivering went to a single industry, agriculture.

ZZ: Like Bruce Babbitt said earlier, it breathed life into the cotton industry. For decades, Pima Cotton, grown in Pima County, was known for being among the highest quality varieties.

And there's also alfalfa. We won't get into it here, but we'll just say go back to season 2, episode 3 of this podcast…and stay tuned for episodes 6 and 7 of this season.

Stacks of hay bales sit beside an irrigation canal in Imperial Valley on June 20, 2023. Critics have called for reductions to the amount of alfalfa grown with Colorado River water. The particularly thirsty crop is mostly used for cattle feed.

Stacks of hay bales sit beside an irrigation canal in Imperial Valley on June 20, 2023. Critics have called for reductions to the amount of alfalfa grown with Colorado River water. The particularly thirsty crop is mostly used for cattle feed.

CC: By 2017, the amount of CAP water used by farms had dwindled down to less than 20%, with municipal, tribal, and industrial uses now accounting for about three-quarters of its delivery.

[music fades out]

But, as Rich Weissinger says, what CAP delivers is raw river water.

RW: We don't do any treating. so the folks that do the treating are, it's important for them to know what the quality is. So they can set up their treatment plants to support that.

ZZ: That can mean everything you'd expect to come in a river, from sediment to . . . residents.

At this point in our tour, we were standing by some large concrete tanks. At that moment, they were empty, but they aren't always.

TW: We do stock fish, I think it's a type of grass carp that we stock in there, as well as catfish. And then there's also natural fish from the Colorado River and Lake Pleasant, bass, other catfish and different lots of different striped bass, largemouth bass, smallmouth bass, it's all in here, crappies, bluegill, they're all in our system. But we stock the catfish and the grass carps to help mitigate some of the algae and caddisflies are the other thing that the cat fish do pretty well at. They like to eat the little eggs or the larva the caddisflies before they hatch, certain times of the year that can be annoying for as this passes through communities."

Fish tanks sit near the CAP canal.

Fish tanks sit near the CAP canal.

Before you get any ideas about casting a reel into the CAP, remember, it's the state's only canal system that's entirely fenced.

I asked and no, not even the employees get to fish in it.

But, with the canal basically being a river, there have been quality issues.

CC: In the late 80s and early 90s, when the CAP began serving residential customers and as Journalist TR Witcher points out, people noticed something, particularly at the southern end of the system.

TW: In Tucson, as soon as they changed the system from groundwater to CAP water, you know, residents in older parts of the city were complaining that, you know, the water was, foul colored or it smelled bad. And so the city passed a regulation prohibiting the direct use of CAP water by residents.

[music fades in]

ZZ: Now, I grew up in Tucson, and I remember this era. My dad had a joke that I'm guessing was a common refrain around the city. When it came to the water quality, he'd say someone removed the R out of CAP. My adolescent brain found that endlessly funny.

Tucson residents eventually had enough, and the decision was made to instead go back to groundwater, and to send CAP deliveries to a recharge station, where the water is pumped into the ground, giving it the same filtration that was received by the water people were used to drinking.

VIEW LARGER Lower Santa Cruz River recharge site for the water bank in the Marana area

VIEW LARGER Lower Santa Cruz River recharge site for the water bank in the Marana area CC: Tucson officials say thanks to that plan, the service area now has a water supply for about 10 years. And even though the metro area has grown to about one million residents it is using about the same amount of water it was in the 1980s.

While CAP water has helped sustain growth in the state's two biggest cities, others have been left, well, high and dry in the process of ensuring the metropolitan areas, which include most of the state's population, are able to grow.

ZZ: Remember how Rich said 80% of Arizonans are served by the CAP?

[music fades out]

When Bill Wheeler recorded his oral history in 2003, he said the next big concern was that other 20%.

The CAP was part of the solution that has let Arizona's population grow in the Phoenix and Tucson areas, but he's concerned about those outside of CAP's reach.

BW: Prescott, Flagstaff and Payson, Sierra Vista, Nogales. These areas still have big problems. Cottonwood, even with the Verde River running through Cottonwood, still has major problems because SRP has claims on some of that water that otherwise Cottonwood would like to divert. There are very heavy problems of balancing the water supply around the state and of taking care of future growth.

CC: All of those areas…and many others…rely on aquifers which by nature are slow to recharge and quick and easy to drain.

Bill was talking about growth concerns back when Arizona had about 5.5 million people.

The most recent Census estimates have that number at almost 2 million more people living in the state.

ZZ: TR Witcher, who lives in another fast-growing Colorado River community, says he wonders if the future in places like Arizona is concern about how we continue to grow while remaining smart with our water use.

TW: I talked to a water manager here in Las Vegas a few weeks ago, at an evening talk or some such. And he said, this community, Las Vegas, they're trying to be more proactive now about identifying businesses, everybody's looking for growth, jobs and whatnot. But identifying businesses that are not water intensive."

ZZ: For years, Arizona, just like Las Vegas, has been very outspoken about being open for business, but TR wonders if that could soon be a thing of the past.

TW: So now, it's an interesting moment. If we've reached the point where we have to say, 'this business, yes, we want to, we want to encourage you to come because you are not using that much water. This business here . . . I don't know how that works.' If you just make it regulatorily so difficult that certain businesses just decide that this isn't the place for them, or whether you just cross your fingers and hope that they pick some other community.

Bruce Babbitt said the first discussion may have to be about the biggest user of CAP or any water in the state, agriculture.

BB: It's inevitable, if we're going to have a balanced water supply, that there'll be a continuing transition from agriculture into urban uses. And the only question is how we manage it consistent with meeting reasonable expectations of the agriculture sector, pricing water appropriately, setting up mechanisms to make the transfers in a fair and equitable way.

CC: But, that gets further complicated when you look at Arizona's water laws.

Water rights aren't necessarily decided by who has the most need or economic impact. They're more likely to be decided on first-come, first-serve or on how things are negotiated.

ZZ: Then, there's a whole other layer of complication that can come when water gets down to the state's southern edges, and water becomes an international issue.

That's next time.

Tapped is a production of AZPM News.

This episode was mixed and produced by me, Zac Ziegler.

It was co-reported and edited by our News Director, Christopher Conover.

Our theme music and some interstitial music is by Michael Greenwald.

Visit our website in the podcast section of azpm.org for pictures, links and more. Thanks for listening.

(music fades out)

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.