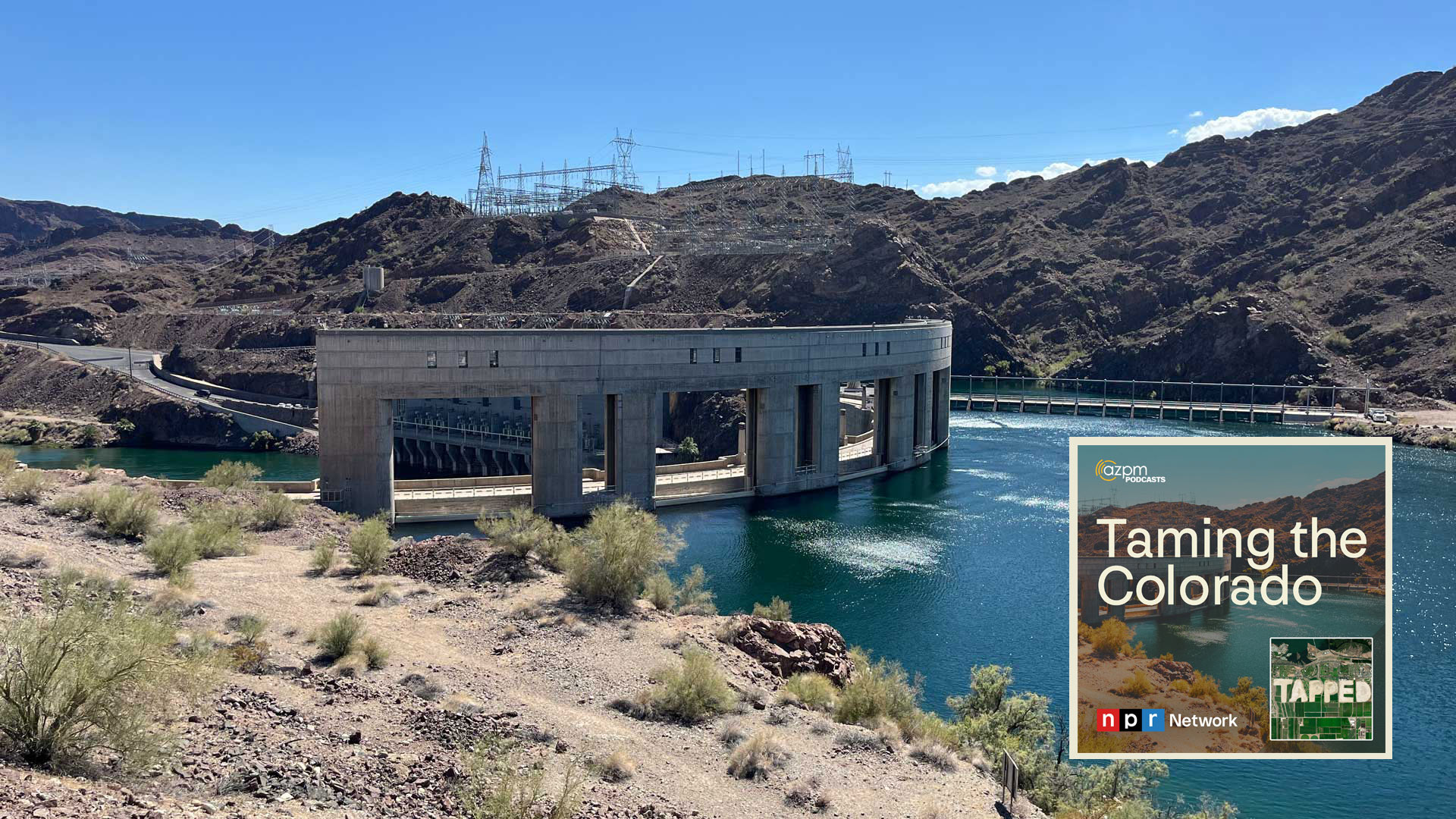

The Parker Dam in Arizona looking towards California. The electric transmission lines from the dam are all on the California side and provide power to the Golden State. The construction of the dam formed Lake Havasu.

The Parker Dam in Arizona looking towards California. The electric transmission lines from the dam are all on the California side and provide power to the Golden State. The construction of the dam formed Lake Havasu.

Tapped: Season 3 Episode 01

The Colorado River is the most dammed river in the U.S. But, before it was a source of water for several states, it was an untamed waterway that ran much differently than the rivers that Americans were used to utilizing farther east. Season 3 of Tapped kicks off by exploring the history of the river's lower stretches, and how a battle over one dam changed Arizona's rights to the river's water forever.

More from Tapped

Transcript

ZZ: We're standing at a spot overlooking Parker Dam on the Colorado River about 124 miles Southeast of it's more well known big brother, Hoover Dam. This dam generates about 457 gigawatts of power a year most of which goes to the pumps in California's Colorado River aqueduct

CC: But for Arizonans, it has a more well-known job. It creates Lake Havasu, a 19,000 acre reservoir that's a recreation site fostering one of the state's fastest growing cities.

It's also a major reservoir where Arizona and California which border either side access their share of the Colorado River. Parker dam was built in the 1930s by the US Bureau of Reclamation, with construction starting before Arizona had ratified the deal that split up the river's water, which led to Arizona's then-Governor sending the state's National Guard to an area that's now a part of La Paz County.

This is Tapped, a podcast about water. I'm Zac Ziegler.

CC: And I'm Christopher Conover. Arizona has spent almost 100 years fighting over Colorado River water and watching as damn's pop up along its western border. While Lakes Mead and Powell are often the focus of attention, they're far from the only reservoirs along this run of the river.

So do all these dams help or hinder the water consumption issues says the river moves towards its terminus?

[music fades out]

ZZ: Arizona is at a point in its history that may end up being a nexus of important decisions about water. So this season, we'll be focusing on a question, how did we get here?

To start, we're asking that question about the Colorado River, especially what happens once it makes its way through Lake Mead and the Hoover Dam.

CC: But, before we get too far into what is going on now, we're going to set the stage with a little history of the river…paying particular attention to a time when the only dams you'd find on the river would've been those made by nature.

TS: "Before all of the dams on the Colorado River, the Colorado really was a transportation highway."

CC: That's Tammy Snook, an historian with the City of Yuma, and we're talking to her at the Colorado River State Histts:oric Park, a location that was once a stopping point along that route.

TS: And starting in the early 1850s, with the first military installation in the Yuma area, which was actually Fort Yuma on the California side of the river. Starting with Fort Yuma the army was bringing steamboats up the Colorado to resupply first the fort and then later the Yuma Depot.

CC: We're sitting in one of the historic buildings on the museum's grounds, luckily it's one that has been updated to include air conditioning.

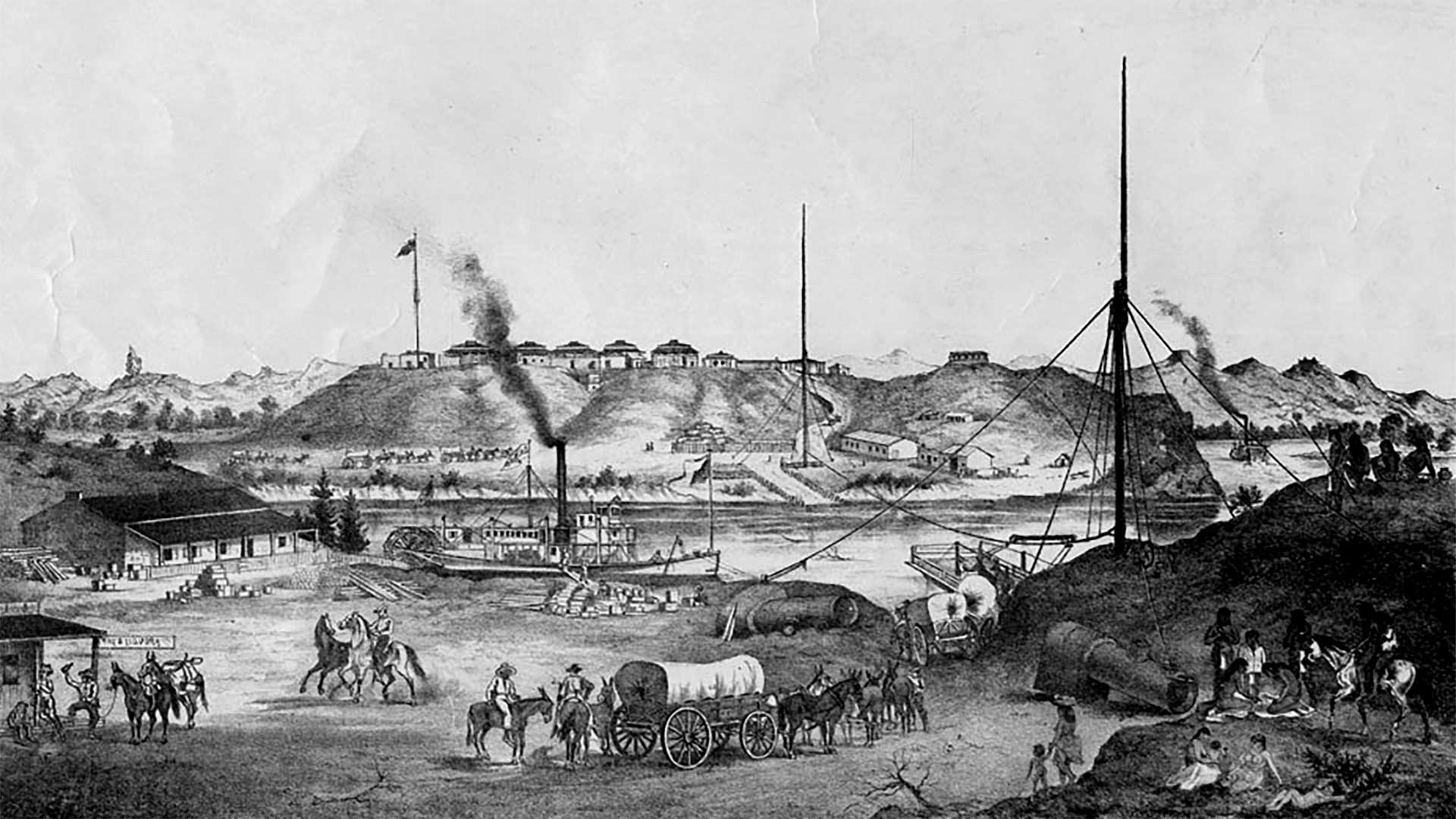

Two walls of the room are mostly covered in large murals by murals that depict life on the river before it was dammed.

The Yuma Quartermaster Depot.

The Yuma Quartermaster Depot.

TS: The murals are showing right at the Yuma crossing area with those two bluffs. So on top of the one Bluff is Fort Yuma. And then on top of the other Bluff is the old Yuma territorial prison.

CC: The bluffs were a spot that squeezed the river, making it easier to cross using ferries. It also made the area prime for settlement.

TS: Fort Yuma was the first permanent non native settlement to be established in the area, and the little village of Yuma grew up around the fort and the trail because of that steamboat access, had access to things that folks in the interior of Arizona didn't have access.

CC: Downright metropolitan

TS: Exactly, yes, really. I mean, you know, having that, that that steamboat or that ability to you know, kind of freight things in whether it's grand piano, which, or just the latest magazines, on women's dress, you know, whatever it may be, you really did have the advantage."

CC: She says boats would mostly come from San Francisco.

TS: They were bringing supplies into the territory from the coast of California. But then on their way out of the territory. A lot of times they were hauling things like or because there were a lot of gold and silver strikes along the Colorado River and that or would be hauled out to be processed elsewhere."

ZZ: Jack Schmidt is the Director, Center for Colorado River Studies at Utah State University.

JS: Ships would come to the Delta offload on the smaller boats, and then navigate through the Delta to Yuma. And we know that Yuma was an inland port. So the river was actually navigable by paddle-wheeled steamboats. Now that isn't to say that they didn't end up marooned on sandbars and hit the bottom and they would do better at some times of the year than others, but the river was navigable."

ZZ: Navigable, but not as routine as rivers with less seasonal flows.

JS: It was one of the most biologically productive places in North America. We know it was a wet world of ever-changing channels of what Aldo Leopold described as a green lagoon. We early descriptions say that the river channels were changing from year to year. And if you went back there to course the river at different times, you take a different course at different times, because a river was jumping from one place to another.

ZZ: Supply depots dotted areas upstream, almost reaching the Grand Canyon, but the farther north those depots were, the more seasonal they became.

CC: That unpredictability made the arrival of the train a welcome advancement.

TS: Railroads could ship things much faster and much cheaper than steamboats could, and of course, they could go in different directions. And so the arrival of the railroads started to erode the steamboat transportation or the importance of the steamboats. But it wasn't until the dams were built on the river that steamboats were no longer able to go up and down the river.

CC: The Laguna Dam was the first to be built in 1909 as part of the Newlands Reclamation Act of 1902, a federal bill that began irrigation canal building in 17 states.

JS: The principle of dams and reservoirs is to eliminate the variability, essentially to make the Colorado River into a boring place. That's like rivers elsewhere in the United States, the big Gangbuster wet years with big Gangbuster floods, you don't want those, you store those in reservoirs, they protect human health and safety, and you store the water for dry times. So you want to even out the flow even out ever, you basically make the Colorado River as unnatural, up place as possible to facilitate its utilitarian development. And that is what we've done.

CC: Laguna marked the end of the Colorado's riverboat era and the start of its era as a means to divert water for agriculture.

[music fades in]

ZZ: Damming of the river continued with two irrigation dams in Colorado in the 1910s.

Then came the Colorado River Compact, the legislation that today is being re-negotiated because it overestimated the amount of water in the river.

The agreement was signed by six of seven states in 1923. Five years later, Congress authorized the Hoover Dam, originally named the Boulder Dam. It was finished in 1936.

But, while work was underway on Hoover, construction on another dam to its south would stir up controversy, and bring armed soldiers to the banks of the Colorado River.

[music fades out]

That story comes after the break.

[mid-show break]

This is Tapped, a podcast about water, I'm Zac Ziegler.

CC: And I'm Christopher Conover.

ZZ: In 1934, crews arrived on the banks of the Colorado River near what was then the Yuma-Mohave County line.

CC: A slight side-track, the site is now in La Paz County, but that county was about 50 years away from coming into existence.

ZZ: This area is rural now, with one good size community, Lake Havasu City, which has about 60,000 people. But back then, it was even more sparsely populated.

Brian Wedemeyer wrote about this incident in 2000 when he was a reporter at the Lake Havasu City Today News-Herald. The headline dubbed it "The Battle for the Colorado."

He went on to become a history teacher, then a principal. He's also a non-fiction author. His most recent book looks at the witnesses who didn't make it to the stand in the O.J. Simpson case.

BW: Lake Havasu City didn't exist. Parker was his little tiny town. There was no paved roads that went up the river towards where the dam site was . . . I interviewed a guy for that story who e he lived on a ranch where now it's all developed with these nice river houses. I interviewed him and he was like 90, 93 or something at the time, but he was telling me how he used to take a burro to school on a little trail.

CC: His name was Bud Graham, and he played a fairly big role in the start of the dam.

BW: He was really the only guy in the early stages that before the dam was built, who could really navigate the river. And I remember him talking about it, him getting approached by these suit and tie Metropolitan Water District guys, and he's out here in the middle of nowhere, and they're trying to find somebody to take him to take them up river.

CC: The district ended up training Bud as an engineer so he could help them find the spot where the dam would be built.

The crews were starting work on another engineering marvel south of Hoover, the Parker Dam.

BW: Everybody talks about the Hoover Dam, but Parker Dam is the deepest dam in the world. And then you had because of what they were doing, sending the water to Southern California, they had this huge 13 mile tunnel that they dug right through a mountain. And you can imagine at that time trying to do something like that, in this weather, it seems almost unbelievable.

CC: He says that on a day where high temperatures in the Parker area had hit 120 degrees or higher three times in the past week.

BW: The Metropolitan Water District was building the dam.

ZZ: That's the water company that supplies six California counties, including the Los Angeles and San Diego metro areas and the agricultural production area known as the Inland Empire.

BW: They were literally in the middle of construction. And the Arizona governor at that time, B.B. Mauer, he wanted some water from that dam. He wanted water for his state and he wanted power for his state. And the Department of the Interior, they weren't making a commitment to that. So what he did was he literally declared martial law at the construction site on the Arizona side.

ZZ: Remember how we said six of the seven states had ratified the Colorado River Compact at that time? Arizona was the hold-out.

BW: He sent down troops to the dam site and set them up on the Arizona side of the dam right there at the Colorado River. And there was even a machine gun detachment. One of the things you have to remember is at that time, there was no highways going through there.

CC: Enter Nellie Bush.

DB: She was a local woman, who, they actually came from the Glendale area. Her and her husband operated the trolleys that used to be in downtown Phoenix.

VIEW LARGER Nellie Bush greeting Maj. Pomeroy upon arrival of Arizona National Guard to Parker in 1934.

VIEW LARGER Nellie Bush greeting Maj. Pomeroy upon arrival of Arizona National Guard to Parker in 1934. CC: That's Deanna Beaver, she's a local historian at the Parker Area Historical Society who has lived in the area for almost her entire life. She has written about Nellie Bush, and the society has some of her personal papers in its collection.

DB: Her personality seems to remind me of some of those, the Sandra Day O'Connor type people, you know? When she was young and on a ranch, and the women just worked alongside the men. She'd do what she needed to do. She wasn't afraid to get her hands dirty, but yet she could dress up and look like a lady too.

CC: Nellie Bush and her husband owned several businesses in the area.

DB: They ended up having two hotels here in this town. First, the small one, and then then the one that they built in 1916 that they called the Grand View. And then from that, you know, she went to the U of A and went to law school down at the U of A and she was a teacher.

CC: She was also the first woman to become a licensed pilot in Arizona and the first woman to serve in the Arizona Legislature.

[music fades in]

But, for this story, one of her businesses and that connection to the legislature would play a role.

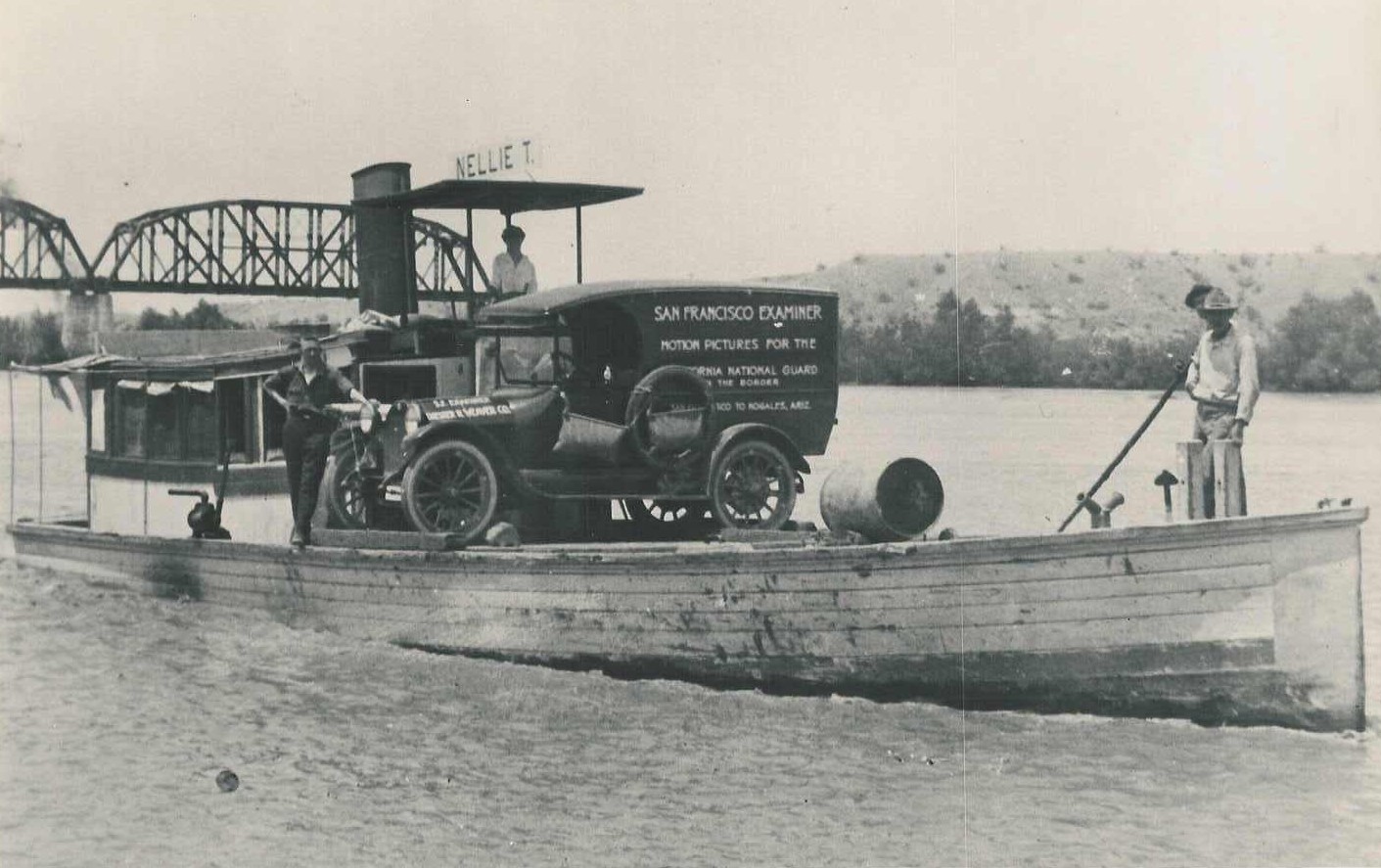

BW: When she heard the governor wasn't having it on this water, she was right there with him to support him. And she ran the ferry that ran across the Colorado River from Parker, over into California, that that right now, there's a bridge there. Well, she got involved because the best way to get these troops up to that dam site was not to go like through Prescott as it was really rough terrain, but to take him on the river and shoot up the river in these ferries. So the governor at that time commissioned her as the commander of the Arizona Navy. So we actually had an Arizona Navy, if you believe it or not, which consisted of two ferry boats.

VIEW LARGER Nellie Bush at the wheel at of the Nellie T during the 1934 incident at Parker Dam.

VIEW LARGER Nellie Bush at the wheel at of the Nellie T during the 1934 incident at Parker Dam. DB: So they ferry the guardsmen, up by the Parker dam on the Arizona side because they were going to keep California from repelling into Arizona. They put the national guard up there. And one of the things in one of the cartoons that was in the Arizona Republic, it said, the biggest battle they had was with the mosquitoes.

BW: There are seasons where the mosquitoes get really bad. And I would imagine at that time, when you think about the Colorado River, it didn't look like it does. Now the dams turn the river nice and picturesque and blue. I would imagine at that time, it was pretty rough and pretty brown and pretty fast. And there was a lot of vegetation. And they were talking about horror stories of battling the mosquitoes but not any humans. It was the mosquitoes that was the big problem for the troops. And one of the lieutenants I think he sends for reinforcements, sends a dispatch to get more mosquito nets.

DB: California never brought any military force over in anything. But it did get squelched until it worked its way up to the Supreme Court. And then Congress enacted legislation that authorized it.

[music fades out]

ZZ: Governor Moeur's actions turned the battle over Parker Dam into a legal case. The case United States V. Arizona had its way to the U-S Supreme Court in March of 1935, with the decision coming at the end of April.

CC: Justices Brandeis and Cadozo joined in the opinion, writing . . .

"Assuming that the stretch of the Colorado River between Arizona and California involved in this case is navigable, Arizona owns the part of the bed that is east of the thread of the stream, and her jurisdiction in respect of the appropriation, use, and distribution of an equitable share of the waters flowing therein is unaffected by the Colorado River Compact or the federal reclamation law."

CC: Arizona won, because Congress had the power to build a dam on a navigable waterway, and not any other body.

ZZ: So, thanks to the steamboats we heard about at the start of the show and Bud Graham cruising his little boat up and down the river either with Metropolitan Water District staff or on his own surveying, there was definite proof that this was a navigable waterway.

Arizona eventually agreed to allow the dam in exchange for approval of the Gila River Irrigation Project, which brings Colorado River water to 100,000 acres of farmland in Arizona.

Lake Havasu, the reservoir that Park Dam holds back, would become a spot where both California and Arizona pull large portions of their Colorado River Water.

CC: In 1944, Arizona became the final state to sign the Colorado River Compact, though it was not done arguing over its allotment. It would again plead its case over river water to the U-S Supreme Court in 1952.

It won for a second time, and Arizona would later name the pumping station that pulls Colorado River water out of Lake Havasu after the attorney who argued that case.

Dams on the lower Colorado continued to be built up until 1966, when Glen Canyon Dam was finished.

By then, the character of the river had completely changed according to Parker historian Deanna Beaver.

DB: My understanding from my father in law, and some of the elders that have since passed, was the Colorado River, at least in this area, which they were exposed to. Ran wide and wild. So the dance kind of contained it, you know, we're more controlled. And it's kind of morphed over time, you know, it hasn't stayed. You know, the, the river is the same flows the same direction. But it's us some purposes to have morphed over time.

CC: Boats hauling freight used to be able to navigate the Colorado River Delta. Today, there's barely ever more than a trickle of water in it.

In fact, about a decade ago, when they allowed some water through in what the called the pulse flow, it was a story that made headlines.

AZPM, which produces this podcast, had a reporter down there for that event.

A "pulse flow," the first stage of a pilot project to bring life back to the Colorado River delta, flooded parts of the delta in Mexico’s Baja California state in 2014.

A "pulse flow," the first stage of a pilot project to bring life back to the Colorado River delta, flooded parts of the delta in Mexico’s Baja California state in 2014.Vanessa Barchfield: The Colorado River delta was once a fertile land of green lagoons and winding channels. The fresh water mingled here in southern end of the delta in Mexico's Baja California state with the salty waters of the Sea of Cortez.

CC: Jack Schmidt from the Center for Colorado River Studies says here we are, 90 years later, and the fight over that water continues.

JS: Right now, the conversation and the negotiations in the Colorado River Basin, live in a world very much stuck in 100 years of precedent in which we define a lower Colorado River Basin and Upper Colorado River Basin, right the upper state basin states, the lower basin states, who's going to get more water who has to make the cuts. You guys down in Arizona take the biggest cuts now. But someday in the future, we will have the courage to have a different conversation.

ZZ: He says that conversation should be about what this limited amount of water's highest usage is. Should more than half of it go toward growing livestock feed? Should we be growing crops when it's 120 degrees out, like Brian Wedemeyer was experiencing when we talked to him? Should we be encouraging some industries over others?

So let's take a closer look at one niche industry that can be big business. It involves a lot of grass, a lot of water, and many would say a good walk spoiled. That's next time.

Tapped is a production of AZPM News.

This episode was mixed and produced by me, Zac Ziegler.

It was co-reported and edited by our News Director, Christopher Conover.

The voice of Justice Brandeis was Andy Bade.

Our theme music and some interstitial music is by Michael Greenwald.

Visit our website in the podcast section of azpm.org for pictures, links and more. Thanks for listening.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.