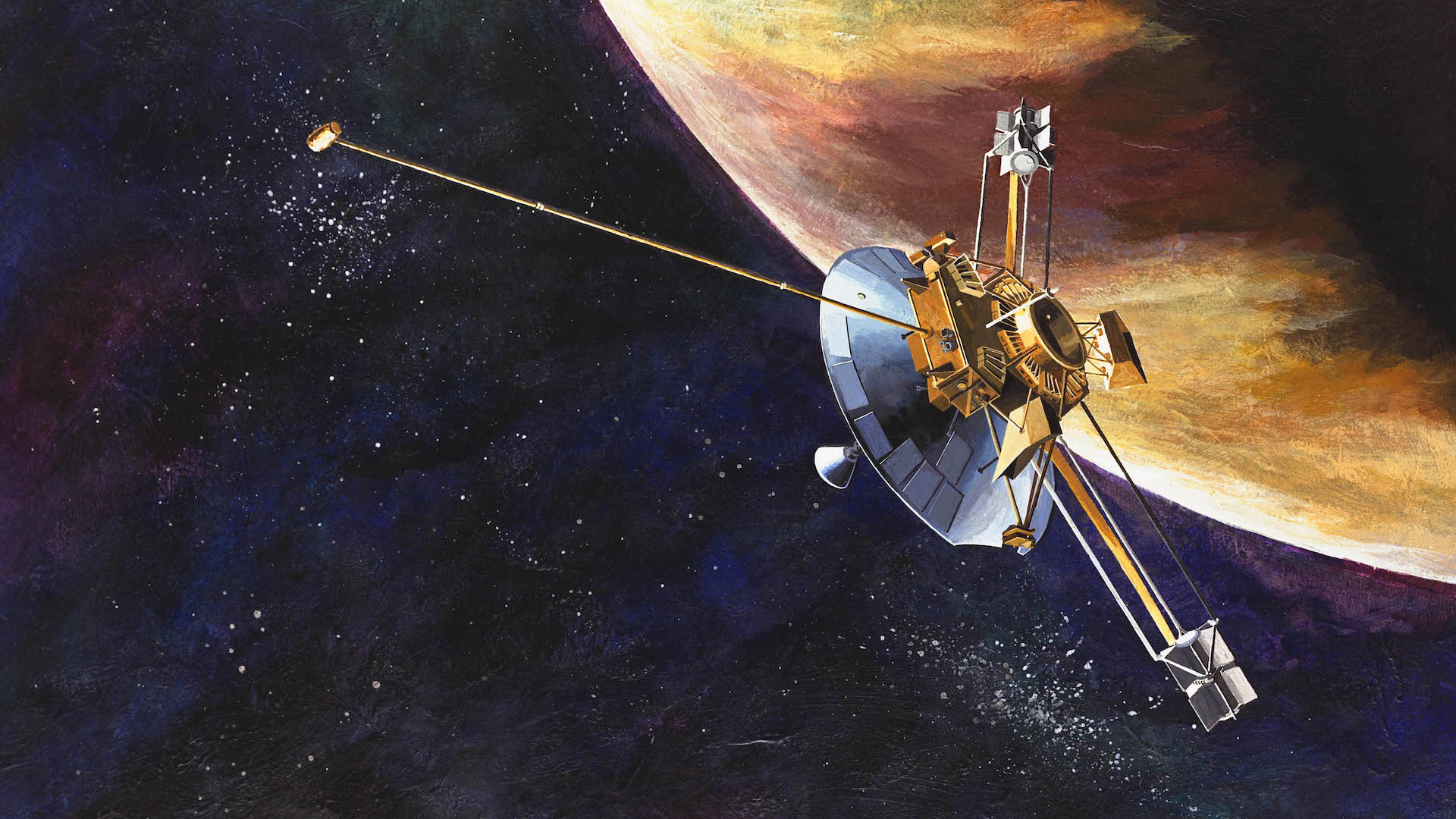

Illustration of the Pioneer 10 unmanned spacecraft.

Illustration of the Pioneer 10 unmanned spacecraft.

University of Arizona planetary scientist Bill Hubbard remembers how the dream of history-making encounters with Jupiter, Saturn, and beyond started. It began not long after the Soviet Union put the first satellite in orbit around the Earth.

Gary Flandrau, a young aeronautical engineer at the California Institute of Technology (unrelated to Grace Flandrau, for whom the UA Planetarium and Science Center is named) had studied the paths of the outer planets. Hubbard recalls Flandrau made an interesting discovery.

“He noticed that the four outer planets, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, were at positions in their orbits where, in principle, you could obtain successive gravitational assists from each of those planets, starting with Jupiter," he said. "And you could complete a tour of those four planets in a reasonable amount of time with a reasonable amount of fuel. And this was dubbed the Grand Tour.”

The Grand Tour was also the name given to a journey aristocratic Europeans took in the 17th century. It was an adventure that would typically begin in London, and take the traveler to Paris, across the Alps in Switzerland and ultimately the streets of Rome. Mark Twain popularized the Grand Tour in his best-selling satire "Innocents Abroad."

As the years passed before the next turn of the century, NASA sought to meet the challenge of pushing a package across more than 500-million miles of deep space.

“The problem was there simply wasn’t enough money," said Hubbard. "The Congress did not appropriate enough money for NASA to build and fly a specific Grand Tour spacecraft even though there was one on the drawing board.”

Hubbard served on a scientific study group that insisted the trip could not wait. It was pointed out that the last time the planets were in this unique alignment was in the late 1700s, when Thomas Jefferson was President.

The compromise was created with the concept of gravity assisted flight: in theory, a satellite could use kinetic energy from the planets themselves – including the Earth - to slingshot itself across the solar system. A journey that would take 40 years to complete could be cut down to ten. NASA approved a previously-designed pair of spacecraft to start the first Grand Tour of the outer planets scheduled for the early 1970s.

Pioneer 10 was launched toward a Jupiter fly-by in 1972, and one of the dozen experiments on board was an imaging system developed by Dr. Tom Gehrels at the University of Arizona. NASA installed a second camera on Pioneer 11 ahead of its follow-up journey the next year. It took each of the twin spacecraft 20 months to travel from Earth to Jupiter and its moons. From there, Pioneer 11 used the slingshot gravity assist method to soar from Jupiter to a fly-by of Saturn. It was the first mission to deliver pictures and data from the ringed planet.

The Pioneer spacecraft were also the first to map the magnetic fields of the two gas giants, and measure the intense radiation surrounding the planets. The gravity assist method enabled the Voyager unmanned missions to complete the Grand Tour concept with encounters of Uranus and Neptune in the 1980s. It has since become the most frequent, practical way to travel to asteroids like Bennu, where the UA-backed OSIRIS-REx pursued its recent sample collection and return mission.

Finally, the Pioneers, along with their robotic cousins from the Voyager program, became the first man-made objects to sail from Earth beyond the orbit of Neptune and enter interstellar space.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.