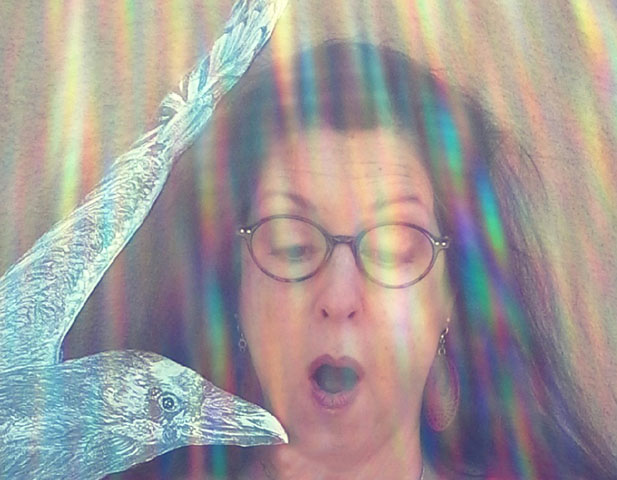

Author and illustrator Beth Surdut listens to ravens, and has paddled with alligators in wild and scenic places. She also knows a place in Tucson where the nightlife is really swingin'...

Paying Attention: Bats ©Beth Surdut 2016

When a bat flies by me, the wing beats kiss my cheek in temptation, and I hear a whispered invitation to learn the secrets of these crepuscular creatures.

My initial search for Southwestern bat encounters brought me into the Ortiz Mountains in New Mexico. Led by wildlife biologist Mike Roedel, six of us waited at the mouth of the old Santo Niño mine. At sunset, under a full moon in a lavender sky, I heard squeaks and rustling amplified by a large metal cylinder lining the vertical shaft. Townsend’s Big-eared bats began to fly out in ones and twos. Wings swooshed by my head as I peered and listened for the next arrivals. About 4 inches long, the bats looked like spirits…with rabbit ears.

Bats are the only mammals that can truly fly. They are of the order chiroptera which translates as hand/wing. Whether designated as megabats or microbats, the bone structure in their wings is similar to human forearms and fingers, if ours were over 9 feet long and our bones could bend. Microbats can locate objects in pitch-dark three-dimensional space by emitting high-frequency sounds that bounce back. Using this technique, called echolocation, they can figure out the texture and speed of an object. And along with these natural superpowers, bats are primary pollinators of saguaro and organ pipe cacti as well as hundreds of species of agave plants.

Unless you are qualified, don’t touch bats. Saying that, I did! After leaving a sacred monkey forest in Bali, I walked by a man working on his front porch. A fruit bat, an old world megabat known as a flying fox, hung like a large umbrella from the railing, watching. I asked in Indonesian if the bat was teman-- a friend. The man smiled, gently hooked the bat over his arm, and moments later, I had broken my rule of not touching wild animals. The bat hung from my wrist as I stroked its suede-soft wings. It seemed to be grinning toothily as it swung up towards my face to get a better look. The closeness of that furry foxy face was a little disconcerting, but oh, those beautiful limpid eyes.

Later, again in Bali, I stood at the entrance of a sacred and very smelly bat cave that looked like a view into a many-storied tenement building. Thousands of bats, tucked next to each other, stacked in rows and clusters, slept, squabbled, interacted. One, who was quite obviously a male, kept presenting to the bat next to him. As he repeatedly nudged her, she tucked her wings tighter around her and over her head as if indicating, “Not now, honey. I’m tired.”

While there is much that I will do to get to the great view, the sacred place, the animal adventure, here in Tucson, I can just go outside.

Arizona boasts 28 species of bats either migratory or year round. There are Lesser long-nosed bats who drain hummingbird feeders each night. I spoke with echolocation expert Janet Tyburec, who lives in Tucson. When I asked if she had local favorites, she said, “Pallid bats! They’re tough, wonderful, and they smell kind of like skunks and look like little pigs.” She explained to me that they could heal fractures by forming the equivalent of an internal walking cast around the damaged part. They especially like high-end neighborhoods here, where they’ll hang over the front door and porches as they eat centipedes and tear the pincers off of scorpions before eating them.

For an impressive and easy view of bats in summer flight, you can visit the migratory Mexican free-tailed bats that fly out at sunset from under the bridge at Campbell Avenue and River Road. Towards the end of July and into August, the numbers escalate as mothers and pups fly together. Tyburec described the pups as “kind of klutzy at first, like kids with learners’ permits.”

Even when you can’t see them in the dark crevices, you can tell where the bats roost by the visible and scented lines of guano droppings. I like to go before dark and wait to hear them wake up. These are social sounds and, in my opinion, a special treat, because humans are not capable of hearing most echolocation frequencies. Spotted bats echolocate between 5-10 kHz-- well within the range of human hearing.

Listen to these recordings supplied by Janet Tyburec:

Here is the Spotted bat in the wild:

This is the same sounds expanded in time and lowered in frequency by a factor of 10:

Bats change the cadence and frequency of their calls when they are approaching an object of interest and need more information quickly.

These are Mexican free-tailed bats also slowed down by 10 times. The slower cadence is basic search phase; the faster ones, approach-phase:

Bats have existed for over 50 million years. With summer temperatures often over 100 degrees in Arizona, we, too, become creatures of the night. Lucky us, who can just go outside, and be enhanced by the wing beats of bats in a star-filled sky.

- Beth Surdut

Thanks to wildlife biologist Janet Tyburec for her assistance.

Want to know more about protecting bats?

Bat Conservation International

Merlin Tuttle's Bat Conservation

Arizona Game & Fish has a free "Bats of Arizona" poster available here.

Visual storyteller Beth Surdut invites you to observe, with unbounded curiosity, the wild life that flies, crawls, and skitters along with us in our changing environment. From exotic orchids and poison dart frogs to local hawks and javelinas, Surdut illustrates her experiences with wild and cultivated nature by creating color-saturated silk paintings and detailed drawings accompanied by true stories.

You can find Surdut's drawings - and true stories about spirited critters - at listeningtoraven.com and surdutblogspot.com.

Beth Surdut's illustrated work Listening to Raven won the 2013 Tucson Festival of Books Literary Award for Non-Fiction. Elements of her raven clan have appeared in Orion Magazine, flown across the digitally looped Art Billboard Project in Albany, New York and roosted at the New York State Museum in an exhibition of international scientific illustrators.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.